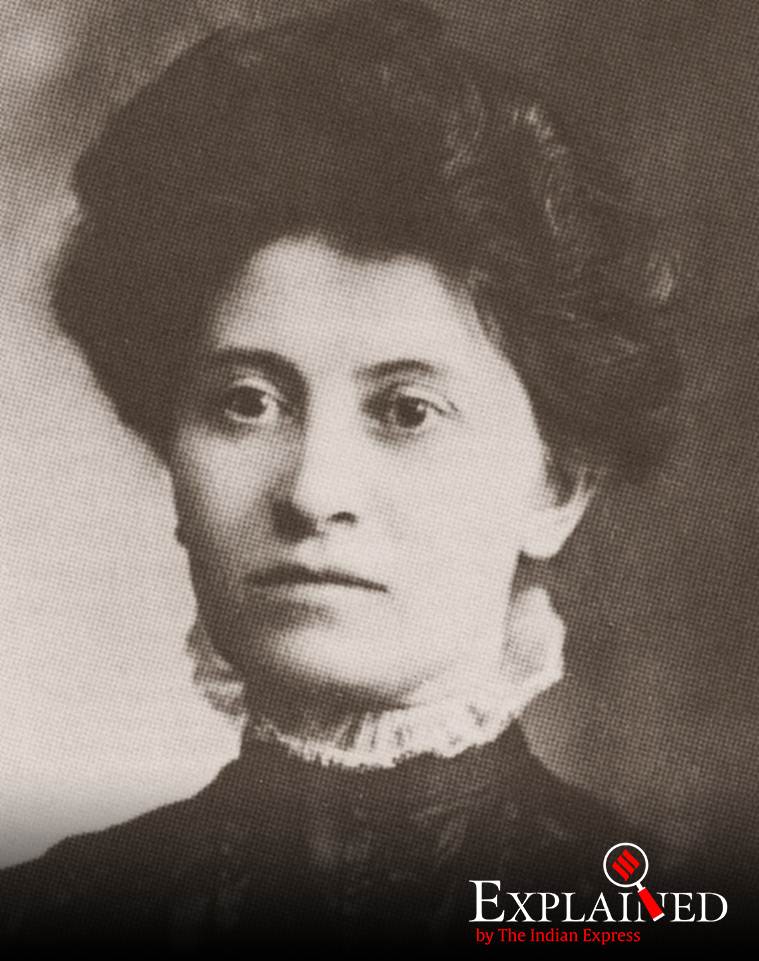

Remembering Theresa Serber Malkiel, the forgotten woman behind International Women’s Day

It was Malkiel who first suggested the observance of a 'National Women’s Day' in the US. It was of crucial importance to her that women have the right to vote. She campaigned for the ballot in New York State and elsewhere.

The first Women’s Day was organised by the Socialist Party of America in New York in 1909. The date they chose was February 28. But over a century later, as International Women’s Day is observed across the world, the woman behind the idea is seldom remembered.

Theresa Serber Malkiel was born on May 1, 1874 in a little town called Bar, in the Polish part of the Russian Empire. Raised in a middle-class Jewish family, Malkiel spent her earliest years in an environment that was fuelling widespread anti-semitism across the Tsar’s empire.

The institutionalised restrictions placed on Jews in the last decades of the 19th century ensured a largescale exodus of the community, primarily to the Americas. Malkiel too landed in the United States in 1891. By then she had been exposed to the clandestine Jewish labour movement, the lessons from which she would apply in her new home in America.

It was Malkiel who first suggested the observance of a ‘National Women’s Day’ in the US, a concept that was soon picked up by countries across Europe. She also had several other contributions to the development of a robust women’s movement in America. She was particularly focused upon the mobilisation of immigrant working women in demanding basic rights and equality. In her later years, Malkiel lent a powerful voice to the movement for women’s suffrage.

Soon after her arrival in the US, Malkiel, like most other migrant Jewish women, found employment in one of New York’s sweatshops. She started working as a cloakmaker in the immensely unregulated garment industry. The following year, she organised the Women’s Infant Cloak Makers’ Union, among the first organisations to focus on the needs of working women.

In her detailed research on Malkiel published as ‘From Sweatshop Worker to Labor Leader: Theresa Malkiel, a Case Study’, historian Sally M Miller notes that during the 1890s, New York City saw the growth and development of several self-help groups to meet the needs of Jewish immigrants.

“This comprehensive institutionalised network was geared to the needs of the families of the ghetto and those of employable men. However, institutions to meet the needs of of single working women hardly existed,” Miller wrote.

Malkiel took up this challenge, and became one of the first women in America to draw attention to the plight of immigrant working women. The union she founded fought fiercely for the rights of women in factories.

However, Malkiel realised soon that economic solidarity without political mobilisation could not deliver results. “For her, socialism became the path to independence, to a cooperative commonwealth of workers which would liberate men and women and establish equality for all,” Miller wrote.

Malkiel was one of the first women to rise from the ranks of factory workers to the leadership of the Socialist Party. In 1896 she was appointed delegate to the initial convention of the Socialist Trades and Labour Alliance. By that time she was part of the Socialist Labour Party; a few years later, she joined the Socialist Party of America.

While the Socialist Party did not bar women from becoming its members and in fact, proclaimed its commitment to ensuring equality for men and women, they did very little beyond this formal acknowledgment. Malkiel realised that they had to work outside the national party in order to address the specific needs of women. In 1907, she started a parallel movement of socialist women. She also indicated the need for a separate national organisation of socialist women.

“Women are tired of their positions as official cake-bakers and money collectors,” she is believed to have said while justifying her stance on a separate organisation.

Also read | Five amazing books by female authors you must read

Finally, the Socialist Party responded with the formation of a women’s department and a Women’s National Committee as its executive body. Malkiel was elected to the committee, and became the “party’s leading immigrant woman activist”. She attended several conventions as a delegate, campaigned fiercely for the rights of immigrant women, and helped mobilise several strikes.

In 1909, she actively supported the Shirtwaist strike in New York. The Socialist Party aided the strikers with funds and publicity from November 1909 until the end of the strike in February 1910. In ‘The diary of a Shirtwaist Striker’, Malkiel described the strike through the eyes of an American-born female worker who eventually finds a sense of solidarity with the immigrant worker in their fight for basic human rights.

Her dream of developing a stronger network of socialist women, however, remained unfulfilled. In 1914, the party leadership withdrew funds from the National Women’s Committee, and the programme was discontinued.