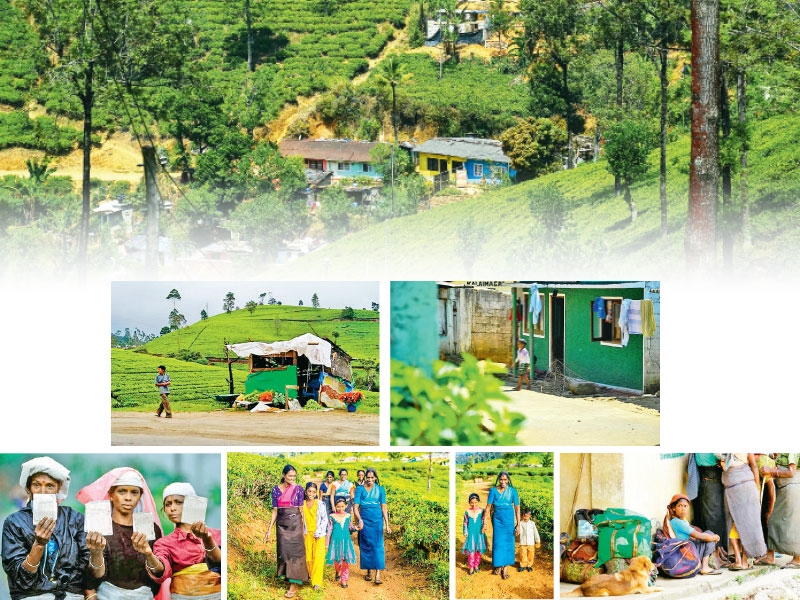

Soaring wheat flour prices hit estate workers the hardest

Families of estate workers, many of whom have a number of mouths to feed, are increasingly skipping meals on a daily basis. Some even manage with only one meal each day. Due to the high cost of rice and the scarcity of flour, estate inhabitants are in a desperate search for money to eat.

The community eat roti made with flour and drink plain tea as their main meals. At present, a kilogramme of wheat costs between Rs 400 and 500 on the black market that the scarcity of flour has generated. After decades of struggle, estate dwellers now make Rs 700 per day after deductions for EPF and trade union contributions from the Rs 1,000 daily flat salary rate.

The anger among the community of plantation workers is still not fully handled, though. The families assert that there have been reports of child malnutrition in the estates. As estate workers are devoted but underpaid employees who help expand one of Sri Lanka’s biggest exports, the issue has not yet been addressed.

It has been two months since Pushpa Rani, a 59-year-old employee at Madawatte Estate in Maskeliya, and her family of nine have received three meals a day. She lamented how the rising cost of kerosene and household products had turned everyone’s lives from terrible to miserable.

“We get paid Rs 1,000, but after Sandha and the EPF, an individual only receives about Rs 700. Most often, we eat roti. It is a staple in our diet. My family consists of ten people, including me, and we require 1 kg of wheat flour to make ten rotis for a single meal. Wheat flour is available in Maskeliya, and it costs between Rs 400 and 500. That means we only have Rs 300 in hand after purchasing 1 kg of flour. This is only for roti that is made for a single meal,” she wailed.

Further, Rani claimed that the cost of vegetables in Maskeliya and Hatton is so high that she is unable to provide her children with the nutrition they require. “My son and daughter fall sick regularly. They are really skinny, and I take them to the hospital at least twice a month,” she said.

With a dozen children to feed, Suppaiyya from Rajamale Estate said they are in desperate need of help and that if an immediate solution is not found, the situation may result in social unrest. According to his salary calculations, they can only manage one meal, and that too only if the roti is eaten alone.

“If we collect 15 to 20 kg of tea leaves each day, our daily pay is approximately Rs 750 to Rs 800. Feeding our children on this budget is quite challenging due to rising food prices. We belonged to two unions, but both the Government and those organisations are useless,” he lamented.

According to Vice President of Protect Union (PU), K. Maithilee, childhood malnutrition is increasing in the estate sector due to the nation’s ongoing economic crisis.

The Vice President claimed that the daily earnings of estate workers were insufficient to cover expenses because of the inflation of necessities and other goods.

With their meagre pay, she said estate employees struggle to feed their kids three meals a day and send them to school. Malnutrition is now a lurking danger in the estate sector. According to Maithilee, children in estates are at risk of losing their prospects for a quality education.

She also appealed to the Government and community leaders to pay attention to this matter and take the necessary steps to put special plans in place to offer benefits to kids growing up in estates.

Failure to do so will negatively affect the estate community’s way of life. To get the Government’s attention and secure the protection of a community that is advancing the economy, trade unions that represent the estate community must speak out, Maithilee added.