UNHRC’s vote against past leaders, not against Lanka

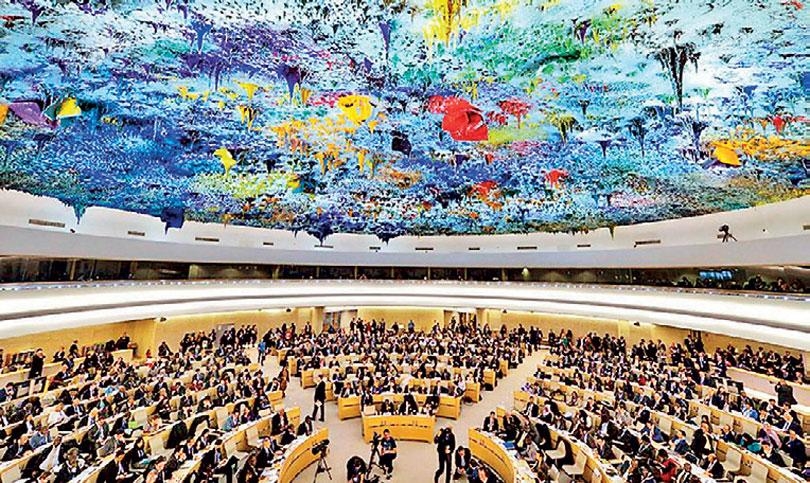

Playing sinner at home could not have been the best possible way to woo UNHRC’s floating member states to cast their vote against the British led resolution on Sri Lanka at the month long 51st session in Geneva which ended on Thursday.

During this biannual pilgrimage at the UN’s Mecca of human rights from September 12 to October 6, the Lankan Government committed two unpardonable blasphemes.

The first was to use the archaic Official Secrets Act and gazette ‘high security zones’ in various designated areas in and around the capital in which even peaceful protests were banned.

This plan, which was gazetted on September 16 by President Ranil Wickremesinghe and issued on September 23, was met with stiff opposition. Fortunately, it lasted for only a week. It was revoked by the President on October 1. But its reversal didn’t amount to atonement for the reverse gazette came too late to win dispensation from the UNHRC. The ghastly cock-up not only left egg on the Government’s face but, worse, it revealed its propensity to crack down on human rights without remorse.

If UNHRC members suffered any doubts on that score, it would have been confirmed by the introduction of the second, the Bill to establish the ‘Bureau of Rehabilitation’, presently going through the constitutional motions to become law.

An Orwellian nightmare is in the making with the Government planning to set up detention camps — euphemistically called rehabilitation centres for the politically misled.

The Bill assumes a paternalist air when it initially states its purpose to be that of rehabilitating drug addicts, ex-combatants, and members of violent extremist groups but takes a sinister and dangerous form when it includes in section 3 ‘any other group or person who requires treatment and rehabilitation’.

The vague references and the absence of any judicial process involved in the operation will empower present or any future governments to arrest even peaceful demonstrators or political enemies and pack them off to rehab camps.

The Bill also provides for its inmates to be ‘used productively to enhance the economy’ and grants immunity to members of the tri-forces using minimum force to compel a detainee’s obedience. This gives rise to the frightening possibility of future dictatorial regimes establishing forced labour camps or Stalin style ‘gulags’ in the guise of rehabilitation. Furthermore, the Bill shrouds the ‘Bureau of Rehabilitation’ in complete secrecy; and makes it a jailable offence to break the silence. The bill is currently challenged in the Supreme Court.

A similar gazette was issued by President Gotabaya Rajapaksa on March 12 last year titled Prevention of Terrorism (De-radicalisation from holding violent extremist religious ideology). The regulations gazetted empowered the Government to arrest and hold any suspected extremist in rehabilitation camps without any judicial process. On August 5 the same year, the Supreme Court suspended the President’s gazetted order to deradicalise suspected extremists.

If these two alone hadn’t sufficed to make civilized nations wince at Lanka’s appalling track record on human rights, then the resurrection of the draconian Prevention of Terrorism Act on August 18 to arrest and detain without charges three activists — involved earlier with the people struggle at Galle Face Green — would have made them wring their hands in despair.

Especially after the Lankan Government had unequivocally promised to the UNHRC at its 50th session in June this year that it will not resort to the much-maligned PTA thenceforth and will use due process in such instance instead. The Government’s total impunity, in attitude and in behaviour, to act as it pleases without any accountability, would have driven the last nail home to seal Lanka’s fate in UNHRC eyes.

None of these crass blunders did anything to mitigate Lanka’s black paganist record but reinforced her image as an infidel who had come to scorn before the UN altar of Human Rights. It’s almost as if the government harboured a bizarre death wish to play truant and die on its sword at the Geneva session.

No wonder the verdict was known even before the voting had begun. The signs that Lanka’s case was lost appeared in the last days of the run-up to Thursday’s vote when, according to Ali Sabry, 23 members made a scramble to add their names as additional sponsors of the anti-Lanka resolution to make it 30, originally sponsored by Britain and 6 other states. It dealt the coup de gras to the Government’s infantile hopes of escaping reprisals, of getting away with murder.

Though nought that Lanka did or didn’t do would have moved the two diehard Chinese and British factions to lessen or enhance their opposition or support to the resolution, it certainly would have tipped the scales to convince the middle-of-the-road floating members that enough was enough.

Thursday’s vote held no surprises. The tally read: 20 nations voted against Lanka, including Britain, the US, France, Germany, Argentina and South Korea which supported the British-led resolution. Seven states voted against the resolution. Among the seven states which supported Lanka were China, Pakistan, Cuba, Eritrea and Uzbekistan. Twenty nations abstained. Among them were India, Japan, Malaysia and the United Arab Emirates.

With only seven States coming out in Lanka’s favour out of a UNHRC membership of 47, it was Lanka’s worst-ever showing at the Geneva sessions on a resolution described as the strongest resolution ever brought against Sri Lanka these last ten years.

With this UN sampling of world opinion clearly demonstrated against Sri Lanka’s stance on human rights, will the Government now change its course to avoid hitting the rocks head-on? Afraid not. Going by what the Foreign Minister said before and after the vote, it seems the Government is hell-bent on pursuing the same old Rajapaksa beaten track of intransigence.

First and foremost, it must be reiterated that the verdict is not against the Lankan State nor against the Lankan people. A great effort is being made to hold out that the verdict is not against a particular grouping or people but one against Sri Lanka as a whole. It is no such thing. It is a denunciation of specific actions taken in the name of the State by past and successive Government leaders who had wilfully violated human rights to safeguard their ruthless grip on power.

And whose rights have they flagrantly flouted? Or continue to flout without remorse purely for self-preservation and to stay in power?

Not the human rights of even foreign prisoners of war or the rights of foreign subjects on Lankan soil but the human rights of their own people: the self-same citizens of Lanka who had elected their leaders to office and had temporarily invested the citizens’ sovereign powers in them to be exercised with restraint for the people’s welfare. Not for those lent powers to be abused by the leaders to hide their corruptions, their failures and their injustices.

Certainly not for successive leaders to invoke draconian laws, they had conveniently provided themselves with in advance, and deploy their armed might to crack down on peaceful protests and stifle the dissent of a people, crying out for justice; and later claim that the crackdown was justified in the national interest and everything was done entirely legally. Therein lies the thin difference between legality and legitimacy.

No doubt the Government will hold the UNHRC verdict as one against Sri Lanka and, even while begging before the west, seeking a quick bailout to rise from its financial bankruptcy, will raise the patriotic flag and boast of safeguarding Sri Lanka’s sovereignty against neo imperialistic forces, and blame western conspiracies for having engineered the UNHRC defeat.

No doubt, too, it will hail China as Lanka’s best friend yet again — as Prime Minister Dinesh Gunawardena recently described the Oriental Dragon as Sri Lanka’s best friend — and praise her profusely for voting against the imperialists’ resolution. But behind the diplomatic soft-soaping, is it purely friendship that makes Communist China such a willing and staunch ally at human rights forums?

Or is it her own self-interest that moves her to defend any State that has ‘human rights’ skeletons rattling in its closet as she has in her own cupboard? China dare not step out of the now discarded doctrine of ‘non-interference in the internal affairs of a sovereign state.’ To make an exception — even if her worst foe was on trial — will be to abandon this outdated doctrine and, thus compromised, accept the millennium’s principle of ‘universal jurisdiction of human rights’, which will allow the world to open her own can of worms.

To cite an example, this same Thursday, India abstained from voting on another draft resolution at the UNHRC on holding a debate on the human rights situation in China’s Xinjian region where more than a million Uyghur Muslims have been detained in ‘re-education camps’. No explanation was given why India did not support the resolution brought against her perennial foe but, perhaps, she didn’t wish to create a precedent to encourage nations to call for debates on how she treats her own ‘Scheduled Castes,’ the Dalits in reservations.

On the eve of the resolution’s vote, Foreign Minister Ali Sabry told the media that the result will be less favourable to Lanka this year. Sucking sour grapes, he gave his excuses for why he had lost the case he had so arrogantly championed. ‘It is not a fair reflection of how all members think of Sri Lanka’ and ‘there was heavy lobbying’ and ‘it was all geopolitical’, were a few of the lame duck excuses rendered.

Was it not the leaders that the Foreign Minister was defending at public expense, in the guise of defending Sri Lanka? Leaders who had denied the Lankan people their rights and robbed them of their freedoms?

For instance, when President Mahinda Rajapaksa told the European Union, during his second term of office, that Sri Lanka could well afford to do without its GSP favoured status for its exports to the EU market if it was dependent upon a clean record on human rights, was he acting in the nation’s best interest or serving his own? Is it not the case that it was these leaders, and not Sri Lanka, in the dock these past twenty-five days in Geneva, with the victims of their actions being the people of Sri Lanka?

Why was Ali Sabry objecting to an independent hybrid court made up of foreign and local judges adjudicating at the trials? This proposal, made by then Prime Minister, now President Ranil Wickremesinghe in 2015, had found UNHRC favour until Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s regime withdrew from co-sponsoring the resolution in March 2020.

Why was Ali Sabry still vaguely muttering that a hybrid court with foreign judges was against the constitution when his President, then Prime Minister, Ranil Wickremesinghe had declared, quoting Article and Clause, ‘that any perceived barrier could be overcome through reference to Article 13 (6) which holds: ‘“Nothing in this article should prejudice the trial and punishment of any person for any act or omission which, at the time when it was committed, was criminal according to the general principles of law recognized by the community of nations.” This Article remains extant in the Constitution despite the 20th Amendment.

Why was Sabry still insisting on the Rajapaksa condition of a Lankans Only panel to impartially hear these highly charged cases when, he must surely know, Government appointed local commissions have long lost their credibility and stand damned not in the eyes of the international community alone but more so in the eyes of the Lankan people.

The resolution, which was adopted on Thursday, also invoked the people’s economic rights, and called to investigate the economic crisis and prosecute those responsible.

Ali Sabry took umbrage at the inclusion of economic rights in the resolution; and even questioned whether the UNHRC had a mandate to do so. Had he done his homework before questioning the UNHRC mandate and its right to call on the Government to prosecute those guilty of corruption, he would have known that the International Covenant of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights entered into force in 1976.

Instead, he sought to trivialise the issue of economic rights, mockingly asking in an arrogant vein, whether, next time there was a slipup in cricket, that too would be raised at the UNHRC.

Isn’t it ironical that a people made bankrupt by corrupt leaders and left destitute and beggared, should also have to pay for the defence of those leaders at an international council? Is it with the people’s mandate that Foreign Minister Sabry tries to shield those leaders from international condemnation?

The decision of this universally accepted United Nation’s human rights forum is indeed a blow to Lanka’s past leaders but a beneficial result to the victims, the people of Lanka in their struggle for equality and justice. The resolution condemns those leaders but, unfortunately, it’s the victims of those leaders’ actions who must carry the cross.

Thus they in turn, for their folly of electing these leaders to power, must atone and repent their transgression and pledge never to repeat the mistake.

They must count their blessings that, if not for their patron saints at the Office of the Human Rights Commission, together with Western Democracies and similar nations, who still bother to promote, protect and defend their human rights against their Governments, they would have had none to espouse their untold plight and would have been left totally at the mercy of their political masters. Slaves that the world forgot.