75 Years of Independence and the Tamils of Sri Lanka

Furthermore, the situation seems to have taken a turn for the worse. Some Sri Lankan Tamil nationalist parties and civil society organizations have declared Feb 4th as a “Black Day” (Kari Naal) and a day of mourning.

It is not clear at the time this article is being written on Thursday evening as to whether a “Hartal” or shutdown will take place but it appears that black flags would be flown in the Tamil areas of the North and East on Independence day.

For anyone being free of colonial bondage, Independence Day would be a day of joy and happiness. But that has not been so for the Ilankaith Thamizhar of Sri Lanka for many, many years.

Many Tamils are not part of the freedom day festivity emotionally and spiritually. Lots of Tamils remain estranged and alienated from the Sri Lankan State still. The resentment manifested currently towards Independence Day is illustrative of that black mood.

It is against this backdrop that this column intends to focus reflectively on the recent past of Post-Independence Sri Lanka and ponder over its future while drawing extensively from earlier writings of a similar nature.

Ilankai Thamil Arasuk Katchi

Independence Day on February 4th being observed as a Black Day of mourning by many Tamils began as a political practice within the first decade of attaining freedom.

The advent of the Ilankai Thamil Arasuk Katchi (ITAK/Federal Party) and the rise of Tamil nationalism in the fifties and sixties of the last century, saw the Tamil polity being asked to treat Freedom Day as a day of mourning.

The rationale was that independence from the British had only resulted in being ruled by the Sinhalese. There was only a change of masters. So, Independence Day was nothing to celebrate, but only to be observed as a black day, it was argued.

These symbolic protests underwent a change after the Republican Constitution of 1972. Thereafter, May 22nd too was observed as a black day. February 4th lost a little of its significance. The symbolism of black flags on Independence Day however continued. The escalation of the conflict and resultant suffering made the very concept of independence meaningless to Tamils. Armed conflict and its impact on the Tamil people was terrible.

Years of perceived oppression and suppression had inculcated among many Sri Lankan Tamils a feeling of alienation in the land of their forefathers.

The Tamil political psyche too has changed over the decades. Tamils saw themselves as being on par with the Sinhalese as a founding race of this nation during the Ramanathan-Arunachalam era; the G. G. Ponnambalam period saw Tamils thinking of themselves as the premier all-island minority; S. J. V. Chelvanayagam years saw the Tamils regarding themselves as a territorial minority of the north-east; the Amirthalingam years and the emergence of the TULF saw Tamils perceiving themselves as a distinct nationality with a separate homeland and the right of self-determination.

Veluppillai Prabhakaran and other Tamil militant organisation leaders led an armed struggle to liberate this ‘homeland’ on the basis of the mandate for Tamil Eelam obtained by the Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF) at the July 1977 elections.

The separatist war waged by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) has ended after the military defeat suffered by the Tigers in May 2009.

The fighting is now over and the country has been unified militarily but whether the country has been united politically remains an unanswered question.

The Tamil perception of sovereignty too differed over the years. The Jaffna Kingdom had lost its sovereignty on the battlefield to the Portuguese in 1619. It was then ceded to the Dutch in 1658; the British took over from the Dutch in 1796.

It was only in 1833 after the Colebrooke - Cameron Reforms of 1832 that pre-dominantly Tamil territories were integrated into a unified Ceylon. Until then they were administered separately.

In 1948, the British transferred power to the Sinhala majority. It has been the Tamil position that the 1947 Dominion Constitution, which paved the way for Independence in 1948, and the 1972 and 1978 Constitutions were all imposed on Tamils without the consent of the majority of their elected representatives.

Tamil sovereignty, therefore, lies within the Tamil nation still and the Sinhala majority has no right to dominate. This viewpoint often stated on political platforms was argued brilliantly by former Solicitor–General Murugeysen Tiruchelvam QC, in courts at the Amirthalingam trial-at-bar case of 1976.

Vanguard of Freedom Struggle

However, Post-Independence political problems should not blind us to the fact that a significant section of the Tamils was in the vanguard of a freedom struggle against the British in the past.

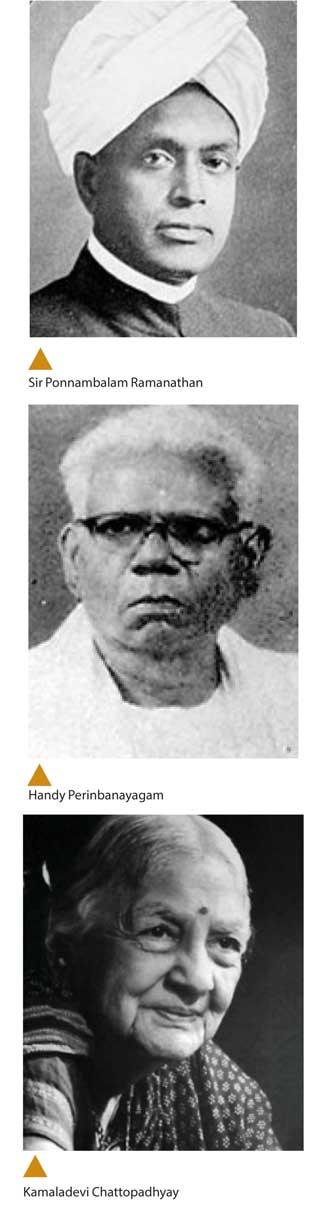

Sadly, the pioneering role played by Tamils in the quest for Independence is now forgotten. From Sir Ponnambalam Arunachalam’s famous lecture on Our Political Needs which laid the foundation for the National Congress to the activities of the Jaffna Youth Congress, Tamil efforts have been praiseworthy in this regard.

The south after the heroic and historic 1818 and 1848 rebellions was generally quiet during British rule. The dominant Sinhala political class preferred to cooperate with rather than confront the British.

Only the Leftists engaged in anti-colonial struggle through protests such as the Suriyamal movement and Bracegirdle Affair.

There was also much trade union activity and strikes. A very large number of Tamils were associated with their Sinhala comrades in these Left-leaning anti-colonial “Aragalayas”.

Trade Union Pioneer A.E. Goonesinghe in his more radical days founded the Young Lanka league to protest British rule.

However, the political path adopted by prominent leaders such as D.S. Senanayake, Sir Baron Jayatilleka and Sir Oliver Goonetilleka was different. They worked for self-rule through negotiation rather than agitation.

As a result, this nation never had an anti-colonial struggle as what was conducted in India by Mahatma Gandhi non-violently, or Netaji Subash Chandra Bose militarily.

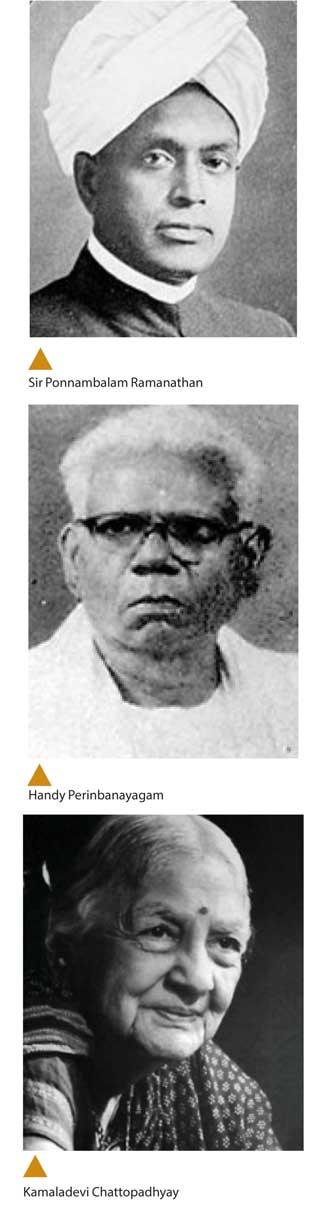

The nearest to an anti-British, pro-freedom struggle, in the country came from the north. It emanated from the now forgotten Jaffna Youth Congress led by the likes of Handy Perinbanayagam, ‘Orator’ Subramaniam, J.V. Chelliah, M.Balasundaram, S.Kulendran, K. Nesiah and C. Ponnambalam.

It was the Jaffna Youth Congress which called first for Poorana Swaraj or complete self-rule from the British and rejected the limited reforms proposed by the Donoughmore Commission.

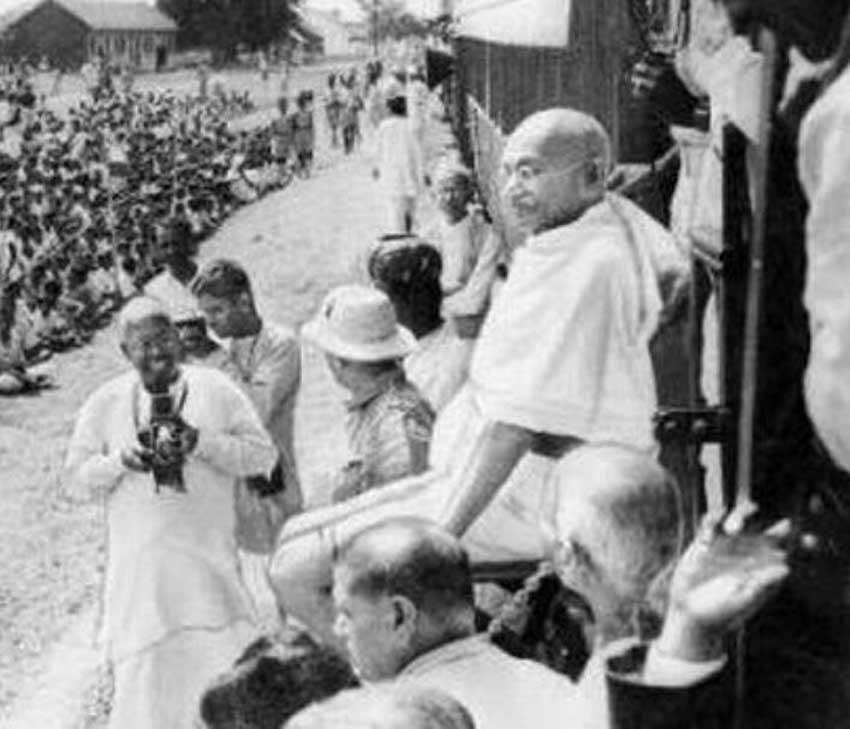

It is recorded that hundreds of Jaffna youths ran about the streets of Jaffna town shouting out loudly “Swaraj, Swaraj” after listening to an inspiring lecture by the famous female freedom fighter of India Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay.

Fired by the ideals espoused by Mahatma Gandhi the Youth Congress demanded Poorana Swaraj (Complete Independence) and urged a boycott of the first State Council elections in support.

When the first State Council elections were held in 1931, there were no candidates from Jaffna. The four seats allocated to Jaffna remained unfilled until 1934.

However, the 1931 boycott was observed only in Jaffna. The rest of the country did not follow suit and the boycott ultimately ended in failure. British scholar Jane Russell compared the Jaffna boycott to parallel developments during the Indian freedom struggle and observed that it was like the turkey-cock trying to imitate the dance of the peacock.

The metaphor was derived from a poem by the poetess Auvaiyaar “Kaana Mayilaadak Kandiruntha Vaankoali”…….

Later, southern historians tried to distort the boycott call and depicted it as a communal cry. Some conflated H.A.P. Sandrasagara’s threat to Ulsterize Jaffna - stated in a different context -with that of the Youth Congress boycott call.

That, however, was untrue. The Youth Congress boycott was inspired by nobler motives. So forceful was the impact of the Youth Congress, that Philip Gunewardena, the Father of Marxism in Sri Lanka’ and the father of Prime Minister Philip Gunewardena, wrote glowingly in the Searchlight journal that Jaffna had given the lead and asked the Sinhalese to follow.

Prof. Wiswa Warnapala reviewing the book written by Santhaseelan Kadirgamar on the Jaffna Youth Congress expressed his admiration of the Jaffna Youth Congress openly and chastised Sinhala political leaders of the colonial period as Bootlickers of Imperialism.

The Youth Congress also conducted several meetings and Satyagrahas, in support of freedom.

They invited Indian political leaders to the peninsula and held mass rallies and processions. Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, C. Rajagopalachariar, Sarojini Nayudu and Kamala Devi Chattopadhyay are some of these.

The Youth Congress also invited several Sinhala personalities from P de S Kularatne to SWRD Bandaranaike to Jaffna for lectures to promote inter-racial amity and unity.

Two noteworthy feats of the youth congress were the boycott of a visit to Jaffna by the then Prince of Wales and the hoisting of the Nandhi flag in place of the Union Jack.

The forerunner of the Youth Congress was the Student Congress of Jaffna formed in 1920 within the precincts of Jaffna College, Vaddukkoddai.

King George the Fifth was reigning then. The Prince of Wales who later mounted the throne as King Edward the Eighth and later abdicated visited Ceylon in 1921.

His visit was boycotted in Jaffna due to the efforts of the Jaffna Student Congress which was re-named the Youth Congress a few years later. The Youth Congress in a symbolic gesture of defiance hoisted the erstwhile Jaffna Kingdom’s Nandhi flag instead of the Union Jack on Empire Day.

What then went wrong in Sri Lanka? Which was the serpent that entered this idyllic garden of Eden?

A number of reasons could be stated and as is the case in matters of this type the blame cannot be laid on one door alone.

Fundamentally the crisis is due to the pathetic inability of ‘Independent Ceylon’ to redefine and re-structure nationhood after gaining freedom.

Sri Lanka is a modern State with an ancient civilisation, but the attempt to define Sri Lanka as a modern Nation State has led to ethnic conflict and political strife.

Power is concentrated with the majority ethnicity leaving the others out in the cold. It is a case of Maha Jathiyata Kiri, Sulu Jathiwalata Kekiri. (Cream for the majority, bitter fruit for the minorities)

The idea of Ceylon was a colonial construct. The British unified the country into a single administration. Sri Lanka was not the only one in this respect. Most countries ruled by the British were their creations in a modern sense.

Ethnic conflict and strife erupted in many countries after the British left. From the Indian sub-continent to Fiji Islands and from Nigeria to Malaysia, there are many instances of this.

Sri Lanka too can be classified as an example of post-Independence conflict within pre-Independence boundaries demarcated by colonial rulers.

Some ex-colonies have reduced and managed ethnic tensions by evolving new forms of power sharing. They have reinvented themselves as ‘new’ nations on the basis of equality and forged a strong sense of common identity.

In the final analysis, the unity and integrity of a nation do not depend on its military strength or structures of governance but on the will of its people. The nation-State is essentially a State of mind.

Estranged and alienated, the Tamil people may feel at present, but there is no denying the fact that they are an integral part of the Sri Lankan nation. Our destiny is intertwined with those of other ethnicities living on the Island.

The future lies not in pursuing unrealistic political goals but in struggling together with all people seeking justice and equality to forge a brave, new, inclusive nation.

It is up to right-thinking members of the majority community to extend their hand of friendship in a spirit of fraternal amity towards like-minded “others”.